Welcome!

Don't mess with my sanitized, air-tight world

I was driving down Fastfood Boulevard in my bubble recently when I began to notice other people in their bubbles.

"We're all in our own hermetically-sealed, self-contained worlds," I thought. "We even have our own climate-controlled atmospheres and entertainment centers suited to our individual tastes."

As I looked at drivers on either side of me — those I could actually see through the tinted windows — my mind continued to expand on the concept. I realized that each of us communicated with the outside world by means of a device that we either pressed to the ear or pressed with our thumbs.

We find our way around strange places by a map on a screen and an anonymous voice that constantly recalculates, based on signals from a bubble out in space.

During morning and evening rush hour traffic, most of the commuter bubbles are singly occupied because we no longer adjust our daily schedules with someone else's. Carpooling was once thought to be a good idea — good for the environment and good for our collective pocketbooks.

Local bus service was as extinct as the dinosaurs until the regional routes were established a few years ago. I rode the bus once and found the riders mostly content to sit in invisible bubbles.

Even drivers on two-wheelers have their own form of bubbles — helmets. Tinted visors make them every bit as anonymous as those in bubble cars.

Maybe I notice these things more since I'm a distance walker/runner. When I exercise, I’m outside, a part of the earth and the air.

When you're outdoors you see and hear more. When you pass someone on the sidewalk or in their yard, you feel the need to speak or throw up a hand.

It's much more difficult to be anonymous when you're out there in the open with nowhere to hide, nothing to blur your image or to insulate your sounds.

That was especially true when I was growing up in the ’50s and ’60s. Not many family cars had air-conditioning so we had to roll down our windows and let in the outside world.

My mother had an Avon route she traveled every day and had to keep her window up so the wind wouldn't muss her hair. But she would pull the little vent window all the way around to allow some outside air to blow on her.

It's no surprise that when A/C became standard on passenger cars, vent windows were a thing of the past.

Cruising the Main Drag back in the day absolutely required having windows spooled down. It was a social function, after all, with carloads of boys and carloads of girls needing an open forum, so to speak.

Blaring AM radios either competed for control of the airwaves or — when everyone was listening to the same station — created a stereophonic jingle: "Thirteen-twenty, W-C-O-G, All-American."

Even the coolest dude on the street — poker-faced in his Shelby Mustang Cobra with a hot blonde in the right seat, allowing his steed to lurch forward as he alternately let the clutch in and out — had all his windows down. Better for everyone to see the rolled and pleated seat covers, customized headliner and, of course, his sideburns and pompadour.

I have this theory — just an idea, mind you — that if we all kept our windows rolled down, turned off the entertainment system and locked the cell phones in the glove box, incidents of road rage would dramatically decrease.

It just seems to me that when you're inhabiting the same world with another driver — rather than enclosed in a sealed vehicle similar to a canopied F-15 strike fighter — you feel more of an attachment to that person. Therefore, you're less likely to cut that person off, lean on your horn or display hand signals that would make grandma blush.

But then again, if you roll down your windows, you run the risk of getting too hot (or cold), being unable to hear your quadraphonic surround-sound or seeing your handheld communications tool blowing in the wind.

I have to admit, it ain't easy being bubble-less.

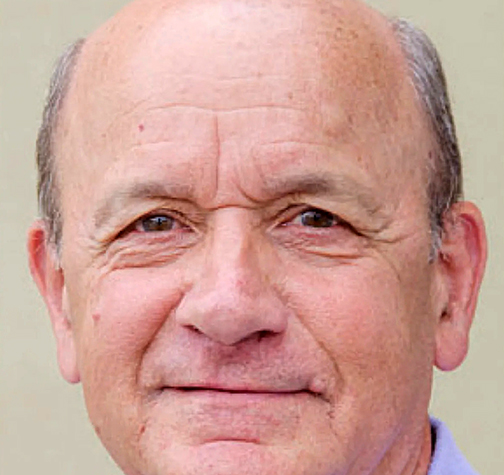

Larry Penkava is a writer for Randolph Hub. Contact: 336-302-2189, larrypenkava@gmail.com.