Welcome!

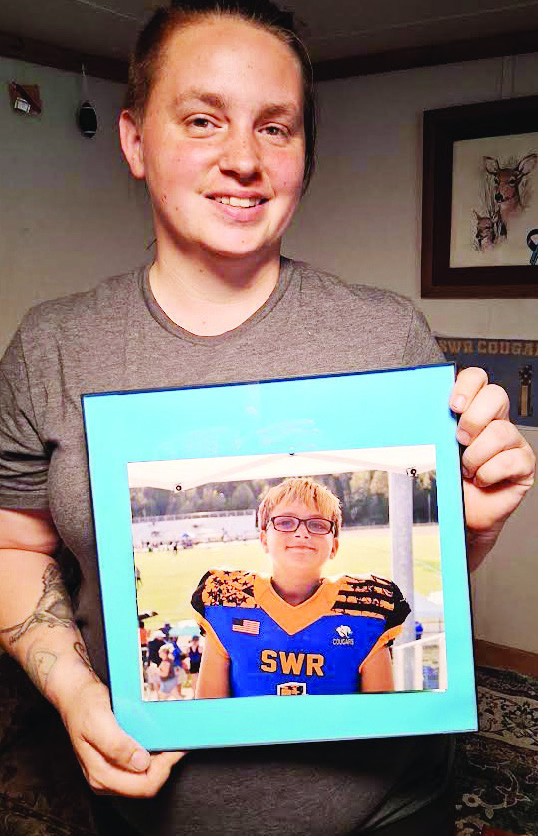

Lori Hunt holds a photo of her late son, Zackery Holley, who died a year ago. She said learned later that his suicide was because of bullying. (Phogo: Larry Penkava / Randolph Hub)

Mom who lost son pushes for suicide prevention

ASHEBORO — Lori Hunt didn’t know that suicide is the second-leading cause of death among youth ages 10-14. That is not until the day after her son, Zackery Holley, took his own life.

He was just 13.

He died Sept. 2, 2024, but it feels like yesterday to Hunt. “I never thought I’d have to say goodbye to my healthy child. It’s been unbelievably hard, especially this week (the first anniversary of Zackery’s death).”

Hunt said Zackery’s suicide was the result of being bullied. He was small for his age and had a condition that caused him to sweat more than normal.

“He was being bullied but he never told me,” Hunt said. “I found out after (the memorial service) when kids said they wished they had said something. He was kidded for his size and his sweating but he laughed it off ’til he couldn’t any more.”

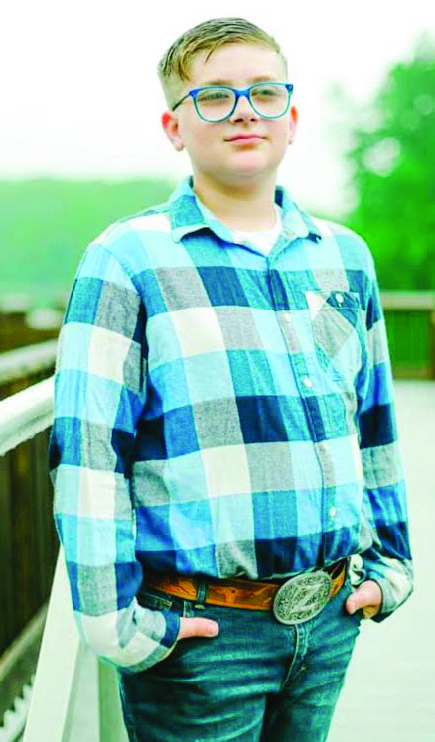

Hunt had written the following in an email to the Randolph Hub: “Zackery was not a kid who was diagnosed with mental health issues. He was in AIG (Academically Intellectually Gifted) classes for math and reading. Zack volunteered at the animal shelter, fed (the) homeless, helped others anytime he could, loved to build and create and play games. He was in church and active in the youth groups. Zack will always be remembered for his smile and his laugh. He was my own personal comedian.”

Zackery was the oldest of seven children in a combined family. Hunt’s husband, Cody, had bonded with his stepson and Zackery treated all his siblings, both biological and otherwise, as family.

“The day after he passed I found out that September is Suicide Awareness Month,” said Hunt, adding that October is Anti-Bullying Month. For those reasons, she wants to make people aware of the problems of youth suicide and bullying.

Hunt said she’s working with the Randolph County School System and Zackery’s school, Southeastern Randolph Middle School, in reference to the anti-bully program.

She would like to see more posters reminding students to be kind to each other and “If you see something, say something” when a student is being bullied or made fun of. Hunt also wants to see posters with the 988 suicide hotline.

To honor Zackery on the first anniversary of his death, Hunt and her children spray-painted Southeastern Randolph’s Spirit Rock in purple and teal, the colors associated with suicide awareness. They have also painted their mailbox, driveway gate and the side of their house near Zackery’s small garden.

Hunt said she joined the school’s PTO in order to have more of a voice against bullying. She’s hoping the school will have an art show for students to create posters encouraging people to treat each other with respect.

During a countywide Suicide Prevention Summit in June, Hunt told Zackery’s story. She was planning to speak to the Randolph County Board of Commissioners during their monthly meeting. She also would like to see much more emphasis on mental health in the school system as well.

“As a mom, never once has anything I took (in preparing for having children) said anything about taking care of their mental health,” Hunt said. “In the last year alone, I have taken several mental health and suicide prevention classes offered in and by our county.

“We stress kids out with (end-of-grade) testing but how to alleviate it is not talked about. People don’t want to talk about it.

“Now I constantly have to ask my kids how they’re doing, and give them an opportunity to share how they really feel. I have to ask them all the time.”

At the same time, Hunt said she misses coming home from work and Zackery asking her, “How was your day?”

“Zack was all about giving back to people,” she said. “He had the biggest heart in a kid I’ve ever seen. I want to be able to help somebody the same way. I’ve taken classes to better myself and my kids.”

She said her 12-year-old son wouldn’t talk for months after Zackery died. He went to a grief camp with other children who had suffered similar losses. At the end of the camp, she said, “My 12-year-old made my jaw drop. He said he lost his brother and it was hard for him. Being able to open up was amazing for him.”

As for Hunt, she says Zackery’s death “eats at me. I’m a mental wreck. I could have kept an eye on him, see he had whatever he needed.”

But she’s working now to help others so they won’t have to go through what she’s living through.

“It’s hard without him. He had said he was nervous about going back to school. I said I would take care of everything. Then he was gone.

“We cannot break the stigma if we are not talking about it.”