Welcome!

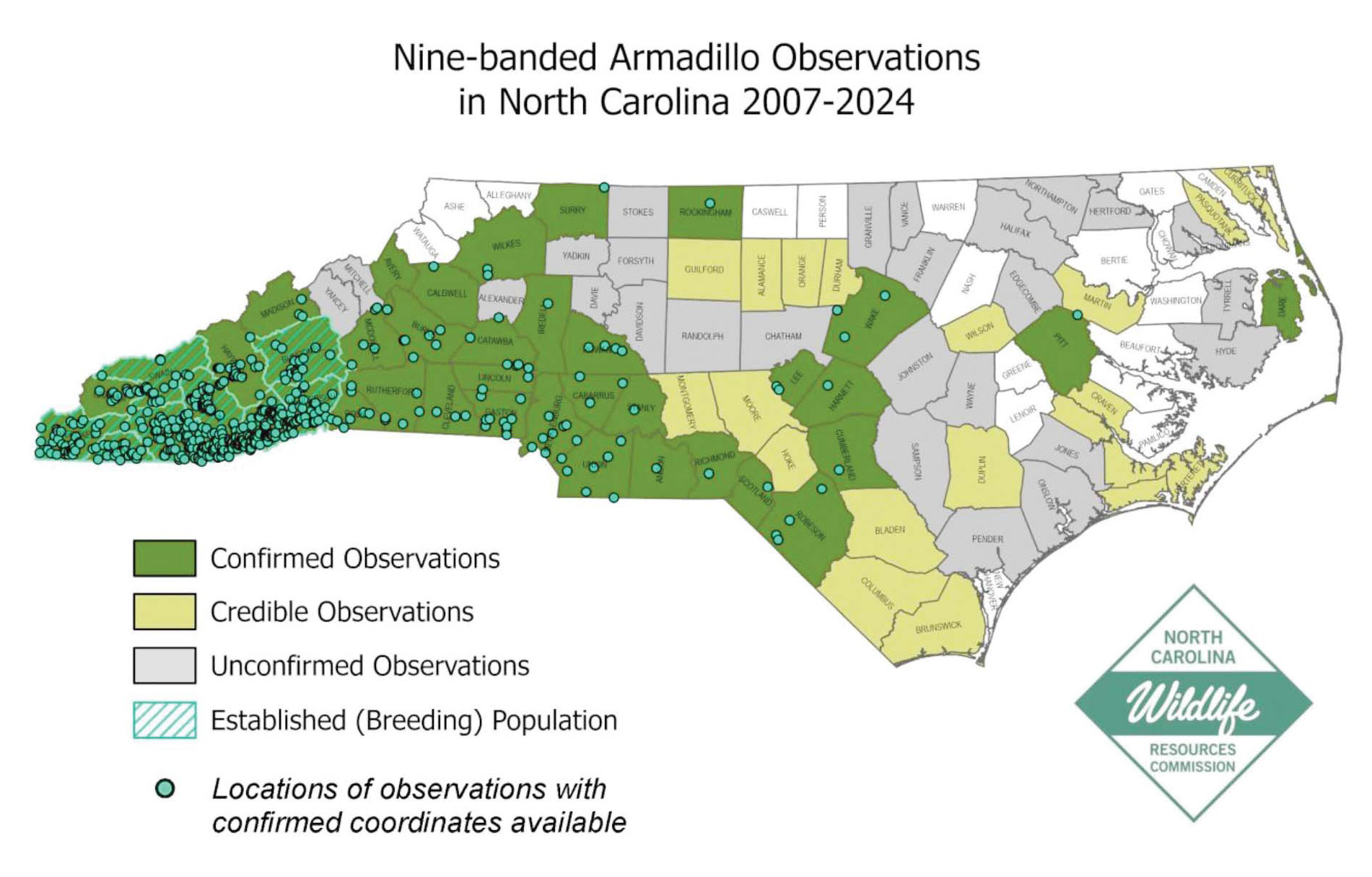

There have been unofficial sightings of armadillos in Randolph County, but judging by the official sightings in counties around Randolph, their migration this way may be inevitable. (Map: NCWRC)

Armadillos on the march toward central NC

What started as a slow shuffle out of southern Texas for the nine-banded armadillo in the late 1800s has turned into a fast-moving, climate-fueled expansion across the Southeast.

Now, it’s brought this armored insect-eater into places it had never been seen before — including right here in central North Carolina.

The first confirmed sighting in North Carolina came in 2007, in Macon County. Since then, the armadillo has steadily marched deeper into the state.

According to the NC Wildlife Resources Commission (NCWRC), more than 1,500 sightings were reported in 2024 alone, spanning 84 counties, with confirmed observations in 40 of them.

While the largest concentration remains near the South Carolina and Georgia borders in the mountains, residents submitted more than 300 observations each year in both 2023 and 2024 alone — the highest totals on record, according to a report from the agency, and marking one of the fastest mammal migrations ever recorded in North America.

Biologists say the number of reports in the Piedmont has jumped in recent years, with credible sightings in Guilford and Alamance counties and unconfirmed observations in Randolph and Davidson counties.

Many of the first reports for central NC come from roadkill. That may sound grim, but it’s a useful clue for biologists who say they often see a spike in road-kill involving armadillos when they start moving into a new area.

Nine-banded armadillos are especially prone to vehicle collisions because they don’t roll into a ball like some of their relatives. Instead, when startled, they tend to leap straight into the air.

Add in poor eyesight and a habit of foraging near roads, and it’s no surprise that 43 percent of sightings reported to NCWRC involved roadkill.

Researchers say warmer winters are a key factor driving the armadillo’s continued expansion north and east. As the 9 banded armadillo has no body fat, historically, cold snaps limited how far the species could spread.

Now with winters in North Carolina and across the southeastern United States no longer as harsh or cold as they once were (this week notwithstanding), the invisible fences that once kept armadillos further south are coming down.

The warmest year on record in NC in more than a century occurred in 2019, according to The North Carolina Climate Science Report. Recent research further confirms the trend of warming winters: A 2024 study found clear evidence that the Southeastern US (including North Carolina) is warming, especially through rising nighttime winter temperatures and fewer freeze events.

These findings are consistent with broader analyses showing long-term warming in minimum winter temperatures and a decline in frost days across the region.

That warming trend is helping armadillos survive — and spread. In a recent study, researchers Brett A. DeGregorio and Anant Deshwal noted that while some states like Kansas have had armadillos for several decades with little change in their spread across the state, North Carolina has seen rapid expansion in just 17 years. “They appear to be rapidly expanding both north (even into Virginia) and eastward,” they wrote in an article in the journal Diversity.

The nine-banded armadillo is the only species of its kind found in the wild in North America. Its name—Spanish for “little armored one” — comes from the flexible bony plates that cover most of its body.

These animals are solitary, mostly active at night, and move slowly while foraging using their keen sense of smell. They’re surprisingly good swimmers, and can even climb fences.

Though armadillos can carry the bacteria that causes Hansen’s disease, or leprosy, cases in humans are rare. Infection rates in the Southeast range from 0 to 10 percent. Still, wildlife officials advise wearing gloves when handling wildlife or digging in soil, just to be safe.

Armadillos use their long snouts, strong digging claws and sticky tongues to sniff out and eat insects — especially grubs, worms and larvae. But those same foraging habits can sometimes cause problems for homeowners. When searching for food, they often dig up lawns and gardens, leaving behind small, shallow holes or uprooted plants.

If you’re dealing with armadillo damage, the NC Wildlife Resources Commission recommends calling its Wildlife Helpline at 866-318-2401. Poisoning them is illegal, and there are no proven repellents.

Trapping is allowed during the regulated trapping season from Oct. 1 through Feb. 28. A license is required if you’re trapping on someone else’s property.

Outside of that window, you’ll need a depredation permit or help from a licensed Wildlife Control Agent.

Catching armadillos isn’t always easy — they don’t reliably go for bait. Experts say your best bet is to place unbaited cage traps along fences, walls, or known travel routes, and use boards to help guide the animal into the trap.

Officials are asking for help from the public in spotting and tracking armadillos. If you see one in North Carolina, you’re asked to email the location, photo and date of the observation to armadillo@ ncwildlife.gov, call the Wildlife Helpline (866-318-2401), or upload your photo to the NC Armadillo project on iNaturalist.

More information about armadillos can be found on the NCWRC website: ncwildlife.gov/armadillo.